The Kwartin Project: Mayn Lebn, Chapter 8

A visit from a traveling cantor and choir ignites a world of fantasy in the mind of an artistic small-town boy.

Meshoyrerim, or cantorial choir singers, were primarily young boys before the age of puberty who sang in choirs with cantors, although an adult bass and tenor were also typical elements of cantorial choirs. A meshoyrer (the singular form) was typically a musically gifted child from an economically disadvantaged background whose family could reasonably expect life as an apprentice to a cantor would provide a measure of stability in terms of adequate access to food and an education in the cantorial trade that could offer a stable future. Being a meshoyrer was a particularly difficult form of apprenticeship because cantors made a large part of their living by touring from town to town, with boy apprentices relying on the hospitality of householders who were strangers. Competition for particularly talented boy singers could be intense and the meshoyrer literature is replete with stories of unscrupulous cantors luring children away from their competitors, or even outright kidnappings occurring, as is documented in the unpublished memoirs of Cantor David Roitman (1884-1943), and in accounts of the life of Cantor Joseph Shlisky (1894-1953). [1]

While the experience of being a meshoyrer was fraught with material difficulties, stories abound romanticizing the anarchic life of performance and comparative freedom of a childhood spent largely unsupervised, with its loose structure lent by musical performance. The musical education of being a meshoyrer typically reached its conclusion by becoming a cantor, but, as Mark Slobin has noted, meshoyrerim entered other fields of music as well, especially Yiddish theater. [2] Luminaries of Yiddish theater including Joseph Rumshinsky (1881–1956), Boris Tomashefsky (1868–1939) and Sholom Secunda (1894-1974) started their careers as child meshoyrerim working with cantors in the Russian Pale of Settlement.

A photo of Sholom Secunda (1894-1974) as a child meshoyrer.

Zawel Kwartin is unusual in that he did not apprentice as a meshoyrer. He was from an upper-class background (within the milieu of overwhelming small-town Jewish poverty in the Pale of Settlement) and his father would not consider allowing him to travel with a rag-tag cantorial choir. As a result, for Kwartin the life of the meshoryrerim, free from the discipline of formal education and focused on music, became an object of fantasy and desire. In Kwartin’s own estimation, inflated perhaps by harmless self-puffery, his talent as a child was remarkable and having missed the opportunity to have performed professionally seems to still have troubled him as an old man.

Mayn Lebn

By Zawel Kwartin

Chapter 8

A cantor with his choir visits our town

I was an eight-year-old boy [c. 1882] when the first true cantor with a legitimate choir of meshoyrerim visited my town. I remember until today when a young man with a goatee came to my father’s store and introduced himself as the bass for Getzel the Cantor from Balta. This cantor and his choir had led services the last Shabbos in Talne and because he had a brother in Khonorod, he would like to come and lead services this Shabbos.

I don’t know what my father and the other householders of the town thought about this opportunity, but my youthful heart was a-tremble. I was feverish with joy that I would finally get to hear a real cantor with a ring of choristers supporting him with the full range of voices. I was longing to hear them, and the sooner the better.

There was business to attend to regarding a trivial matter: where to lodge the cantor and choir while they were in our town. The cantor’s brother, who had recently become the bathhouse attendant in Khonorod, sent the bass to my father. First of all, he knew that we owned, may the Evil Eye be gone, a lovely home with many rooms and enough space for everyone. And secondly, who was a bigger lover of music and cantors than Sholom Kwartin?

The bathhouse attendant was not mistaken. My father quickly volunteered. The next day, the cantor arrived with ten meshoyrerim and they were soon sent to us. You can easily imagine how a little critter like me went running around amongst the band that arrived at our house, ignoring my usual duties. [3]

I can reveal here that as a boy of eight to nine years old, my alto voice was extraordinarily beautiful. In my entire later career of over fifty years as a cantor for the Jews, I have traveled around the world and heard countless choirs, and have had my own choir in cities including Ekaterinoslav, Petersburg, Vienna, Budapest and New York, and have heard children singers in the 1000s—I have never heard a voice like my own in my childhood period.

I remember that evening when Cantor Getzel from Balte and his gang of meshoyrerim conducted their first audition for us in our house. I was completely inflamed with expectation. I couldn’t hear what people said to me. I was listening to the notes resonating in our house and around the streets of the town, both the sweet and false notes. I believed at that moment that there was no greater joy than being a meshoyrer for a cantor. If I could have the luck to be a meshoyrer, that would have been alright by me.

An image from the YIVO Archive of a cantorial choir in Estonia in the early 20th century.

After the audition with the choir, my father mentioned to Getzel that he should take a listen to my voice. The cantor said, “Alright kid, let’s hear what you can do.”

Say what you will, I was not a shy one. I stood up and sang through “Tsur Yisroel” by Cantor Leybele Khirik, or Shapiro of Uman. I had learned this piece from Aaron Hodes, one of the four home-style prayer leaders of the town.

The cantor along with his entire ensemble had wide open mouths, and ears. Apparently, they were completely flummoxed to hear a youngster with such skill in “Hebrew” and with such a sound and resonance. My father and mother, understandably, were standing to the side dripping with pride. Their child was singing, not for some non-Jews gathered under the window, but for a real cantor known to the wide world. If the cantor said a good word, it was understood it came from a real maven, not the small time Khonorod locals.

I remember how my mother said to my father, “Sholom dear, see how our preemie has rewarded all of the suffering we endured on his account with such pride.” [4]

Cantor Getzel was enthused and said to me, “Well sing another one, boy.” I sang “V’hogen B’adnu” by Abraham Shokhet, the cantor of Talne, that I had studied with my uncle Eliezer. [5] Tevele the Alto used to sing the solos in Getzel the Cantor’s choir. Tevele the Alto was known as the best singer in the entire region and was well known to the mavens. [6]

After this “V’hogen B’adnu,” Getzel the Cantor strongly congratulated my father, who had been blessed with a child the likes of which he had not heard before. Getzel said, “In a few years you should remember the words I’m saying now, Reb Sholom.” Getzel continued, “Do not neglect this fortune God has given you. You have to understand what you have to do with your child.”

Getzel the Cantor spoke with my father for a long time. In conclusion, he said, “Listen, Reb Sholom, give me the child for two years and I guarantee you he will be heard around the world. In regard to his religious education, you can rely on me. I will protect him as though he was my own child. He will lack for nothing. “

My father was the kind of Jew who did not like receiving advice, especially not coming concerning such an important matter as how to raise his own child. He was accustomed to having people come to him for his advice. It was distasteful to him that the wandering cantor had the audacity to make him such a proposal, but he didn’t let on how he felt. He politely thanked Getzel for his gracious offer to make his son a “man,” but, he strenuously emphasized, he alone was responsible for his own child. He could not allow his child, who was not yet nine years old, to go wandering around the world, experiencing hard times, eating at stranger’s tables, not receiving the appropriate Jewish education.

However, he did not make a straightforward refusal. He gave a suitable pretext: In two or three weeks, the Kontakaziver Rebbe would visit Khonorod. My father was one of his fiery followers. Once a year, the Rebbe would visit his Chassidim in the surrounding small towns, to dispense advice and receive offerings. Since the Rebbe, God willing, would be coming, he would ask his advice to help him decide what to do. [7]

As a characteristic vignette of the time, I will remark that the honorarium for the cantor and the choir was raised from the pledges made by wealthy householders to be called up to the Torah. [8] Since a lot of people from the neighboring town of Torgovitse had come to hear the cantor, the Torah reading was divided into many sections. Everyone who was called up to make a blessing made a pledge according to his means, and many donating beyond their means.

I clearly remember that Sabbath, when Getzel the Cantor led the prayers for us in shul. The service was extended until two in the afternoon. Every worshipper considered it his duty to offer his appraisal of the cantor. The Jews smacked their lips. How sweet his prayers were! The whole town was running around in circles. It was not a small thing, a cantor coming for the Sabbath.

After the service, all of the wealthiest men took home a meshoyrer to his Sabbath feast. The cantor himself came home with my father. After mealtime, when the older folks lay down for a nap, the young people filled up the marketplace, where people go for walks. All of the attention was on the meshoyrerim. The tenors and basses stood together, surrounded by a ring of small-town “singers” who wanted to show that they too were no slackers.

In the evening at the usual Melave Malka [Hebrew, escorting the Queen; a feast after the end of the Sabbath] at my house, the cantor and choir were in attendance. [9] They didn’t need to be begged and delivered one composition after another. Each piece was accompanied by a delicious toast with liquor. The house was surrounded by people from both towns, and non-Jews as well, including the mayor and the deacon, all standing underneath our window. In honor of the authorities, the cantor sang “Bozshe Tsariya Khrani” [Russian, God save the Tsar; the Czarist national anthem]. We honored the mayor and the priest with a Jewish toast, which they did not disdain.

At the end of the Melave Malka, the cantor, the meshoyrerim and all of the other assembled guests requested that I chant a “shtograf,” that is, I should improvise something. I sang “V’khulam mekablim” and “Yishtebakh,” [10] and again I heard people expressing blessings and the prophecy that here was a future cantor. Getzel again told my father that he would take me, and again the conversation went nowhere.

The next day the town shamas [Yiddish, synagogue caretaker] came to us to pick up the cantor. Together they visited the shops and homes to redeem the pledges Jews had made yesterday in shul. On Monday, Getzel and the ensemble left our town.

The cantor and choir leaving left an open wound in my childish heart. The following days, I walked around in a haze. At night, my childish fantasy got lost in the wide world together with Getzel the Cantor and his assistants. Together with them, I wandered the small towns singing in the choir, and I felt with all my senses how people were enraptured with me, delighted by my voice, and it felt good.

This was all just a dream. In reality, I still went to school, but my mind was not on what the rebbe [Yiddish, religious elementary school teacher] was teaching me. I constantly remembered the stories Getzel the Cantor had told about the great cantors: Yerucham Hakatan, Nissi Belzer, Betsalel Odesser, and others. [11] I went about hypnotized.

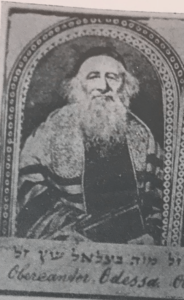

A picture of Betsalel Odesser from the 1937 Zamelbukh of the Khazones Farbund in New York.

I remember that at that time I stopped eating and began to lose strength. My mother took this to heart, and with her tearful voice she asked me, “Zebulon, is something making you sick?” How could I explain to my mother that nothing was wrong? What was causing me pain was only the desire for the small-town cantor Getzel and his gang of meshoyrerim who had appeared like a whirlwind over our small, peaceful town. They had awakened in me longings to wander together with them and to sing and sing, myself not understanding the reason why.

NOTES

1. See Michl Gelbart, Fun Meshoyrerim Lebn (New York: M. S. Shḳlarsḳi, 1942); Kevin Plummer, “Historicist: Torn Between the Synagogue and the Concert Hall,” Torontoist, December 13, 2014; David Roitman, Autobiography of David Roitman (unpublished, n.d.).

2. Mark Slobin, Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982) 21, 31-47.

3. In the original Yiddish, Kwartin describes his distracted excitement with the idiom “vi baym taten in vayngorten,” literally, like a father in a vineyard, which, according to Michael Wex, is an insult directed at lay-abouts. See Michael Wex, “Yiddish insults,” Michael Wex [web blog], November 15, 2009.

4. As Kwartin details in Chapter 1, he was born premature and in extremely poor health, causing his parents tremendous anxiety and heartache.

5. Leybele Khirik and Abraham Shokhet of Talne are biographical blanks at the moment, but apparently were well known cantors in Ukraine at the time of Kwartin’s childhood. Ostensibly, they are sources Kwartin drew on in his recordings of these prayer texts, Tsur Yisroel and V’hogen B’adnu, which he recorded in later decades. Kwartin’s Tsur Yisroel, recorded in Vienna in 1908, was one of his best-known records from before the First World War. In 1921 Kwartin recorded Hashkivenu as a double sided 78rpm record; the second side of the record begins with the words V’hagen B’adnu (one of the verses of the Hashkivenu prayer text) and constitutes its own stand-alone piece.

6. These two sentences about Tevele the Alto are oddly out of place and perhaps are the product of a mistake in the editing of the original text. Or perhaps, Kwartin wrote these lines to suggest that Tevele was threatened by his performance that so captivated Getzel the Cantor, Tevele’s boss.

7. Note that the same Yiddish word rebbe is used both as the honorific for a Chassidic Rabbi, and as the term for a religious elementary school teacher.

8. An aliyo, plural aliyos, literally ascension, is the Hebrew word used as the term for being given the honor to be called up to recite the blessings before and after the reading of the Torah. Auctioning off aliyos is a traditional method of fund raising in synagogues. Because carrying money on the Sabbath is forbidden by Jewish religious law, pledges are made for aliyos that will be redeemed at a later time. Typically, the Sabbath Torah reading is divided into seven sections, but for this special cantorial Sabbath, the Torah reading was divided more times so that more honors could be given and more money raised to cover the expense of the cantor’s fee.

9. In Chapter 3 of Mayn Lebn, Kwartin relates how his family hosted a big party every week for the Melave Malka which doubled as a kind of town hall meeting for local Jewish merchants.

10. V’khulam mekablim and Yishtebakh are elements of the Sabbath liturgy that are frequently employed as musically marked moments in cantorial prayer leading.

11. Yerucham Hakatan (1798-1891), Nissi Belzer (1824–1906) and Betzalel Odesser (1770-1873) are three of the best-known mid-to-late 19th century Russian cantors. For biographical sketches of these figures see Samuel Vigoda, Legendary Voices: The Fascinating Lives of the Great Cantors (New York, N.Y.: S. Vigoda, 1981).