20th Century Events in Salonica Retold in American Sephardic Song

Sephardic Americans sing about Jewish participation in the countercoup (1909) following the Young Turk Revolution (1908) and lament the disaster following the Greek Revolution that spelled the beginning of the end of the Jewish community in Greece.

Jews from Salonica (Thessaloniki), the city with the largest Jewish population in the Ottoman Empire and Greece, migrated in scores to the United States before the First World War, making New York City one of the major diasporic hubs that connected Ottoman-born Jews across the globe. [1] Sephardic immigrants maintained several Salonican cafés in New York City to provide a space for collective organizing and fundraising for Jews in need in their hometown. [2] While these cafés were known for hosting political activity, they also were recreational gathering places with musical ties.

The following two songs document two significant events in Ottoman Jewish history in Salonica. The first was used the 1909 countercoup led by the Committee for Union and Progress to end the rule of Sultan Abdülhamid II and restore the reforms of the 1876 constitution. The second tells the Jewish experience of the 1917 fire that destroyed 9,500 homes and displaced 70,000 people. [3] Immigrants from the Western Ottoman Empire and Greece to America carried these songs with them—as testified by Emily Sene in her notebooks of song lyrics and archival recordings in Southern California and Isaac Angel in his commercial recordings from New York City. These songs appealed directly to transplanted “Selaniklis” in societies such as the Ermandad Salonikiota de Amerika (known as the Salonika Brotherhood of America and later renamed the Sephardic Brotherhood of America) that organized to help the victims of disasters in popular places such as The Salonika Restaurant and Café. [4]

Background

Before the destruction of its Jewish community in 1943, Salonica was known widely as the “Jerusalem of the Balkans.” Most of the residents of the city center were Jewish. When under Ottoman rule, the dominant language of the city was Judeo-Spanish. The Jewish community remained largely autonomous in the transition from the Ottoman Empire to Greece. The State recognized Jews as a religious minority, affording Jews power over education, the courts, and rabbinical/communal functions. Frictions between secular and religious figures played out in the definition of community structures, decision-making, and representation. Tensions surrounding the use of language were also present: Turkish was the language of the Sephardic Jews’ home after Expulsion as well as the language of Anatolian Greeks, Judeo-Spanish was primarily the language of the popular press, French was the academic language as well as a language often used for commerce, and the process of Hellenization pressured the Jews to speak Greek. The formation of the Second Hellenic Republic in 1924 pushed many Jews to emigrate. While some remained in Greece, others fled to the Ottoman Empire, Palestine, Western Europe, Great Britain, and the Americas. Salonica’s Jewish leadership was split among identities with which the population contended: traditionalists in the Mizrahi party, loyal socialists, and Zionists that promoted the Yishuv in Palestine. There remained a vibrant Jewish community in Salonica until the ultimate demise of the Jewish population in the second world war. In addition to internal fractions, the Jewish community navigated its own identity in contrast to the other religious communities, between which tensions heightened as time progressed.

Under Ottoman Rule

The Hamidian regime had already brought fractures in Jewish identity within the Empire: Zionists, anti-Zionists, socialists, liberals, supporters of the new government, opponents of the new government, and more. These simultaneous identities were clamoring during the 1908 revolution and the 1909 counterrevolutionary coup in a Jewish community with relative autonomy that had flourished for centuries. During the 1909 coup, Ottomans took to the streets crying that the constitution was in danger. With censorship laws lifted, the press had horizontally connected Ottomans, allowing group efforts for reform. [5]

The song “Mansevos de los kazales” was written as a military march for a Jewish unit of the “Hareket Ordusu” (known as the “Armada de Aksion” in Ladino). [6] Istanbul’s 1909 revolutionary coup forced Sultan Abdülhamid II to reinstate the parliament as per reforms of the 1876 constitution. [7] The Young Turks had promised freedoms and enjoyed the support of non-Muslims. Islamists pushed back against secularism. Another opposition group, the Committee of Union and Progress, had become a powerful force in the government. They were instrumental in the formation of the Jewish unit and in recruiting volunteers from Macedonia to travel from Salonica to Istanbul to attack the Islamic rebellion (“Para Estambol vamos/a partir kon los malos” or “We are leaving for Istanbul/we are going to fight the bad guys”) and dethrone the Sultan (“Al rey viejo abasharon i presto/Nominaron al rey djusto en la Turkia” or “They beat the old Sultan/And quickly appointed a just Sultan in Turkey”). [8] This took place during a complicated time in which the government pressured Jews to show public support for their Ottoman brothers (namely, Muslims and Christians), while simultaneously distancing themselves from Christian communities that had conflict with the administration.

Isaac Sene, a Sephardic Jew born in Edirne, Turkey, performed “Mansevos de los kazales” in Southern California. His wife, Emily Sene, transcribed lyrics to aid his memory during his performances at the “Turktown” Picnics in Southern California up until the 1980s.

There had long existed competition between Jews and Christians within the empire as both religions worked to create connections with the Muslim leadership and maintain safety against the powers of the government. During the war of 1876 with Serbia and Montenegro, Jews and Christians in Istanbul marched down the street in different uniforms to distinguish themselves from each other. During the Russo-Turkish War in 1877, the Ladino newspaper La Esperanza told parents to sacrifice their children and send them to battle for the empire’s good. Discussions of spilling one’s blood (see “nuestra sangre va korrer/por amor de la Turkia” or “our blood will run/for the love of Turkey” in the above lyrics) for the empire were commonplace among non-Muslim leaders at the time. [11] In 1896, there were large-scale massacres against the Armenian people at the hands of Turks and Kurds in response to the burning of the Ottoman Bank by an Armenian revolutionary group. Their rabbis warned Jews that had sheltered Armenians neither to admit it publicly nor to donate to Armenian relief funds because it would have put Jews in an unfavorable position in the eye of the Sublime Porte. Keeping a distance from the Armenian community became the safe option when faced with the fear that the Jewish community could suffer a similar attack at the hands of the State. [12]

Jews volunteered for the Ottoman army in the 1897 war with Greece (see “Nos izimos volontarios / Nos fuimos al askerlik” or “We volunteered / We joined the army” in the above lyrics), some wearing the fez to show their Ottomanism, while others proclaimed their wishes to convert to Islam out of patriotism. [13] However, patriotism was no longer neutral when the Jews had to situate themselves against the Greeks and Armenians of the empire. [14] At that point, Civic Ottomanism had amassed a darker meaning as Jews worked against other populations to maintain favorability in the eyes of the Sublime Porte. These tensions continued to build over several years while the desire to end absolutism in the government and bring back earlier reforms grew. When the 1909 mutiny of Macedonian troops in Istanbul caused an uproar among Islamic fundamentalists, Committee of Union and Progress members fled to their base in Salonica. Sympathetic to the CUP, the Ottoman army formed the Action Army to march to Istanbul after failed negotiations between the opposing sides. Amidst this countercoup was the Adana Massacre, a month-long series of pogroms in the Adana vilayet directed against Armenians and Assyrians, resulting in over 20,000 deaths. [15]

Emile Sene’s fragments of “Mansevos de los kazales” were a part of American Sephardic musical heritage that groups likely sang to relive the cohesion that soldiers experienced during this and later events. Her lyrics are consistent with the claim, indicated by other scholars, that CUP supporters may have also used the song during the countercoups during the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 that preceded World War I.

Under Greek Rule

Tensions continued between Jews and Christians after the transfer of Salonica to Greece following the first Balkan War in 1912. The interwar period has been recorded both as a time of flourishing and as a time of decline. Still, historians agree that the fire of August 1917 was the beginning of a series of Greek blows to its Jewish population. The fire ultimately evicted its victims from the city center, where they had once existed as a cohesive network. It allowed the government to replace the old Turkish quarter with a Greek national (as opposed to Ottoman) city built in the European style. Singer Isaac Angel, a Sephardic immigrant from Salonica that settled in New York City, provided us with important testimony from that time. Having previously recorded a 78rpm in 1923 under the record label Palomba Record and Talking Machine Co., Angel later developed his label, Angel Record Company, in Brooklyn in 1924. On his label, he recorded the song widely known as “Cantiga del Fuego” under the name “El Fouego” (1924). [16] It is unknown whether Isaac Angel left Salonica because of the fire. Still, problems encountered during the reconstruction of the city center were a substantial cause of Salonican immigration to America. (See lyrics to “El Fouego” here.)

Isaac Angel “El Fouego”

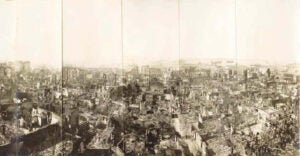

The 1917 fire destroyed most of the ancient city where Jews had predominantly lived. The lyrics state that the fire broke out at “Agua Mueva,” also known by its Turkish name “Horhor Su,” which stood for the northwestern quarter. The fire was reportedly started in a kitchen by a woman cooking eggplant (though this remains unproven), which then spread to an area of hay that ignited a flame that progressively sprawled the old city. In Salonica, there were no public firefighters, only subscription-based private firefighters with inadequate equipment. By the time British firetrucks arrived, they could not fit their trucks down the narrow streets. Additionally, the city suffered reduced water levels due to drought and malaria, leaving firefighters little to do to stop the fire. The Allied forces controlled the water reserves and refused to divert water from their barracks and hospitals toward the fire. Salonica was left with almost nothing with which to fight the flames. During the blaze, German planes, to which the “doves” in the lyrics could be referring, flew overhead, further terrorizing the city’s inhabitants with the threat of bombs. [19] The British stopped the fire the following day at the famous White Tower. The French saved the Customs Office and convicted several soldiers of looting. [20] Refugees carrying their most valuable belongings were sent to the suburb of Dudular, the location of the Allies’ General Command Headquarters, for medical examination. Upon arrival, the refugees discovered that the British forces had plenty of water that they could have used to save the city. Sephardim commonly believed that God started the fire to punish a woman for cooking on Shabbat. Another song titled “El dio la mate esta Grega” claims that the woman was Greek rather than Jewish. Its lyrics, “May God kill the Greek woman who burned the eggplant / She burned down Salonica and left us poor and charred,” [21] illustrate the depths of the conflict between the Jewish community and the Greek population.

Map of Jewish Quarter of Salonica

Photograph of the 1917 fire in Salonica

Below are two recordings of the song from the Emily Sene Collection. In the first, an unidentified man sings. In the second, a woman known only by her first name, Sarah, recites the song from memory.

Immigration from Salonica to America significantly increased in 1920 (The US government reopened its borders in 1920 following a pause during World War I. [23]). Frustration stemming from the Greek government’s theft of the torched Jewish land in the city center was a leading cause of emigration. The 1909 countercoup and the 1917 fire were significant events in Salonican history that colored Jewish feelings of belonging when Jews were torn between two lives under Ottoman and Greek rule. Those who left for America enjoyed vibrant cultural scenes in New York, Seattle, and Los Angeles. Those who stayed in Salonica through the following decades ultimately perished in Auschwitz. Today, the US holds a larger population of Salonican Jews than Thessaloniki itself, as remnants of Salonican culture live on in the daily lives of many.

References Cited

[1] Naar, Devin. 2015. “Turkinos beyond the Empire: Ottoman Jews in America, 1893 to 1924,” Jewish Quarterly Review. 176.

[2] Naar, Devin. 2007. “From the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ to the Goldene Medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States.” American Jewish History 93:4. 465.

[4] Naar, Devin. 2007. 468-9.

[5] Michelle Campos. 2011. Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine. Stanford. 139.

[6] Nassi, Gad. “El Batalyon Djudio en la Revolusion de los Turkos Djovenos.” eSefarad. Accessed May 2020. .

[7] Cohen, Julia Phillips and Sarah Stein. 2014. Sephardi Lives: A Documentary History, 1700-1950. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 140.

[8] Cohen, Julia Phillips. 2013. Becoming Ottomans: Sephardi Jews and Imperial Citizenship in the Modern Era. Stanford University Press. 105.

[9] Nassi, Gad.

A version also exists in the notebook of Emily Sene, a Sephardic amateur archivist in Southern California born in Edirne, Turkey.

[10] The translation is my own.

[11] Cohen, Julia Phillips. 2013. 38.

[12] Ibid. 75.

[13] Ibid. 98.

[14] Ibid. 92.

[15] Suny, Ronald Grigor. 2015. “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”: A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. 171.

[16] Bresler, Joel. 2008. “Isaac Angel.” Sephardic Music: A Century of Recordings. Accessed May 2021. https://www.sephardicmusic.org/labels/Angel/2001-2,2002-2.htm.

[17] These lyrics are a portion of what was recorded by Emily Sene. Sene, Emily. 1989. Emily Sene Collection. University of California, Los Angeles Ethnomusicology Archive. Los Angeles.

Sene added “2” to lines that were to be repeated.

[18] Translation by Giacomo Valentini and myself. [19] 2017 August 25. “Great Fire at Salonica: Simultaneous Outbreaks, Terrible Scenes, Panic-Stricken Inhabitants.” The Brisbane Courier.

[19] 2017 August 25. “Great Fire at Salonica: Simultaneous Outbreaks, Terrible Scenes, Panic-Stricken Inhabitants.” The Brisbane Courier.

[20] Papastathis, Charalambos K. and Evanghelos A. Hekimoglou. 2010. “The Great Fire of Thessaloniki (1917).” Thessaloniki: E.N. Manos Ltd. 13-14.

[21] Saltiel, A. and J. Horowitz. 2001. The Sephardic Songbook. Frankfurt: Peters.

[22] Emily Sene Collection. Ethnomusicology Department, University of California Los Angeles.

[23] Naar, Devin. 2007. “From the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ to the Goldene Medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States.” American Jewish History 93:4. 455.