Bas Sheve: Joshua Horowitz Elevates an Interwar Yiddish Classic

Composer and klezmer musician Joshua Horowitz brings new life to a forgotten Yiddish opera.

In August of 2019, an interwar Yiddish opera received a revival at the Marek Edelman Dialogue Center in Łódź, Poland. The work in question was Henekh Kon’s opera Bas Sheve. Composed in 1924 to modest success, the piece completely disappeared until a piano-vocal score was obtained at an auction by Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg professor of Jewish Studies, Diana Matut. Astounded by the discovery of this presumedly lost work, Matut commissioned composer and scholar Joshua Horowitz to create a new orchestration for Kon’s opera. A tri-national collaboration between the Ashkenaz Festival, the UCLA Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience, and Yiddish Summer Weimar will produce the North American premiere of Henech Kon’s opera Bas Sheve in the summer of 2022.

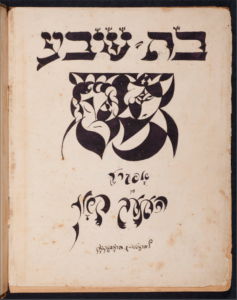

The title page of Henekh Kon’s Bas Sheve.

As Horowitz discussed in a comprehensive interview with poet Jake Marmer and musician John Schott conducted around the time of the initial premiere in 2019, Kon’s piano-vocal score was not only missing orchestral parts—it had an even more glaring lacunae. Sixteen pages of the score were gone, pages that represented some of the most crucial dramatic elements of the plot. The scene in question involved the confrontation between King Dovid and the Prophet Nosn, in which the prophet speaks truth to power and condemns the king for his rape of Bas Sheve and murder of her husband. Not limiting himself to a stance of recreation in his work, Horowitz composed new music for the dramatic climax, working with a new libretto by renowned Yiddishist Michael Wex. In his interview with Marmer and Schott, Horowitz explained that his contribution to the piece was inspired by new curatorial approaches to the presentation of damaged antiquities.

An excerpt from the 2019 performance of Bas Sheve

Rather than seeking to obscure the fact that an artefact is damaged, his approach highlights the distance between the original and his own perceptions of the meaning, intent and aesthetic limitations of the fragmentary original. Horowitz’s contribution to Bas Sheve works towards imagining a Yiddish operatic avant garde that did not have the chance to develop in its original European context. His work departs from the first steps of early 20th century Yiddish musical forays into the realm of European elite music, that were often dependent on the model of well-known Romantic and late classical repertoire, offering instead a robust fantasy of Yiddish experimental opera that is only now coming into view, a century later.

Joshua Horowitz is perhaps best known as a member of the klezmer trio Veretski Pass, alongside his wife, violinist Cookie Segelstein, and bass player Stuart Brotman. Veretski Pass is a long running mainstay of the Bay Area klezmer scene. Horowitz plays tsimbl and push button accordion in the band. The group’s sound derives from a deep investment in historically informed performance. At the same time, some of their best received projects are highly experimental and forward thinking in their formal sophistication. Recent albums, such as their 2019 release The Magid Chronicle, a collaboration with clarinetist Joel Rubin, saw the group exploring the ethnographic collection of Sovet-era Jewish ethnomusicologist Sofia Magid (1892-1954). The album displays a balance of commitment to the materials and creative performance energy. This dialogue of imperatives is essential to doing vital work with archival artefacts that are fragmentary by their nature.

Druzi-Tants from the 2019 Veretski Pass release The Magid Chronicles

Horowitz lived in Austria from 1984 to 2001, first as a student of composition and music theory at the Academy of Music in Graz, and as an active participant in classical music and klezmer scenes. Horowitz was a founding member of Budowitz. Founded in 1995, Budowitz were pioneers in historically informed performance of Jewish instrumental folk music. Through the cultivation of relationships with elder Jewish musicians, such as Majer Bogdanski, they were able to develop an aesthetic built around a conception of Eastern European Jewish folklore grounded in historical evidence and living practitioners. This approach offered an alternative to the contemporaneous klezmer scene in New York that was typified by genre blending and cross-cultural fusion projects.

Mindlins Redele, from Budowitz’s 2007 release, Budowitz Live, their last album.

Long before the massive treasure trove of the Vernadsky Archive in Kiev was digitized and made available online, the klezmer revitalization community was troubled by a distinct paucity of material. This was an especially serious issue for Horowitz and his like-minded community of musicians seeking to reanimate performance techniques and repertoire from historical sources. As Horowitz told me, “When we started, a new tune was gold. We would go to another country to get a new tune.”

In an era when the internet has revolutionized access to sounds of the past, Kon’s Bas Sheve is “the last gasp of the rare,” in Horowitz’s turn of phrase. But while the impulse to protect the past resonates with Horowitz’s work in the klezmer revitalization world, Kon’s opera presents a different set of aesthetic opportunities. Bas Sheve is a Yiddish entry into the trans-national arena of prestigious opera. It is in dialogue with the repertoire of elite European art music and as such offers opportunity to call upon aspects of his training as a composer that may be unfamiliar to fans of Vertski Pass.

Horowitz’s new orchestration and new compositional interpolations into Kon’s score are reasons for celebration on many levels. Horowitz has created a fascinating and beautiful work. This collaboration across history connects two artists and two historically distinct listening communities in the experience of the Yiddish language reconfigured as a medium for the dramatic experience of opera. Crossing the divide of history figures prominently in approaches to Jewish music; in the Horowitz-Kon collaboration, we are fortunate to see the exploration of heritage resulting in sophisticated artistry, heightened in its sensitivity to problems of aesthetics, the construction of Jewish musical identity and the pursuit of the ineffable in music.