From the Archive: Gershon Sirota’s First Recording Session

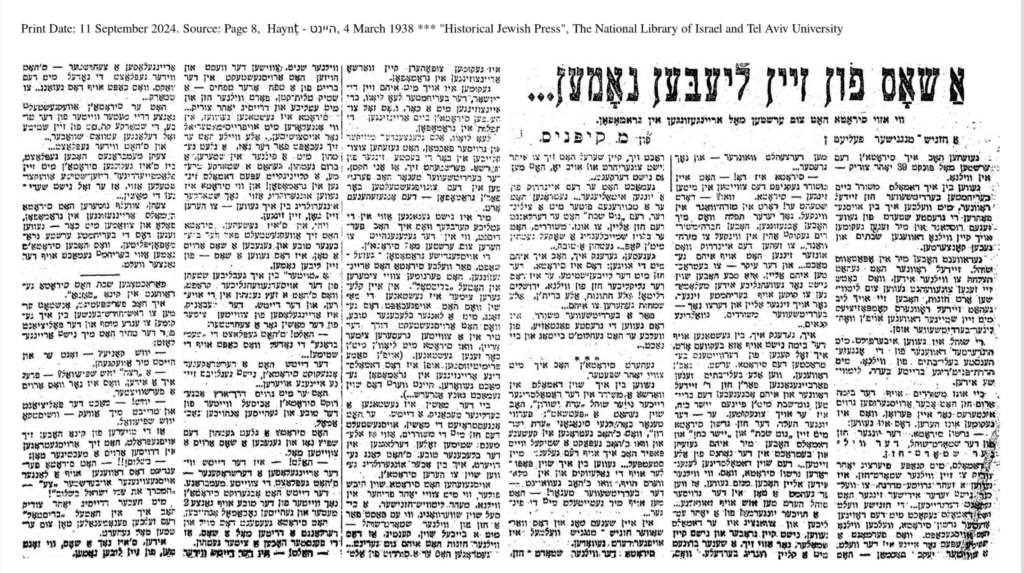

In an article published on March 4, 1938 in the Warsaw daily Yiddish newspaper Haynt (Today), critic and musician Menachem Kipnis (1878-1942) offered a firsthand account of the first recording session of Cantor Gershon Sirota in Warsaw in 1902. In this post, I offer a translation from the original Yiddish of this important document; the article itself, accessed from the National Library of Israel Historic Jewish Press online archive, is included at the bottom of the page.

At the time of his first recording, Sirota was the chief cantor of Vilna. He presided at the prestigious Choir Shul, which was considered a proving ground for cantorial giants. Sirota was spoken of as a generational talent; even before he made his first records, his voice had already attracted attention throughout Jewish Eastern Europe. Kipnis first met Sirota as a child meshoyrer (cantorial choir singer). Sirota occupied a place in the fantasy life of Kipnis and his fellow choir members. Meshoyrerim, who frequently led lives of hardship and deprivation, looked upon Sirota’s artistic and material success with awe. Kipnis’ description of Sirota is pointedly physical, dwelling on details of his body and dress, in the manner of celebrity journalism.

The story of the first Sirota recording session bears an interesting similarity to accounts of the first recordings of Louis Armstrong. Kipnis tells almost exactly the same story of the almost superhuman strength of the masterful soloist that appears in multiple accounts of Armstrong’s first session with the King Oliver band. Both Armstrong and Sirota are asked to stand further away from the recording horn than the rest of the band by the flummoxed engineer, proving their artistic power through the “scientific” measurement of the recording. The acoustic recording apparatus described in the article preceded the more sophisticated electrical recording process that became the industry standard in the late 1920s. The comparatively crude physical mechanism of singing directly into a horn that funneled reverberation to a needle making an imprint on wax was well suited to loud musical instruments that created a powerful signal. Sirota’s voice however, according to Kipnis, was so strong it could barely be contained on wax and caused wax disk after disk to be ruined.

Kipnis, as I have written about in other posts in the Conversation blog series, was a frequent commentator on cantors and the culture of synagogue music. His writings on cantors at times veered into an ironic tone of chastisement for perceived ethical breaches related to commercialization of sacred music. This was particularly the case in his reception of American cantors, who he saw as being prone to the curse of self-adulation in the service of capitalistic public relations.

In contrast to his sometimes-scathing responses to American recording star cantors, Kipnis’s account of Sirota’s first foray into the commercial market of the recording industry seems to be straightforwardly celebratory. The gramophone, rather than being viewed as oppositional to the experience of the sacred, seems to only add to the mystique of Sirota. The machine can barely contain the vastness of Sirota’s masterly physicality. The mythic nature of his voice, which could make windows shake in their panes, is described by Kipnis with a mechanical and militaristic metaphor, as a shos fun zayn lieben nomen. This phrase in Yiddish translates literally as “a shot from His beloved name.” Zayn lieben nomen is an affectionate Yiddish version of the Hebrew Hashem, a euphemism for God used to avoid pronouncing the sacred name outside of the context of prayer. In the translation I gloss this as “a blast from the Name of God.” The image draws attention to the paradoxes of Sirota’s massive tenor voice, that possessed a rugged, almost violent power, and yet was capable of intimate communicative qualities that he attained in his performance of sacred music.

The article focuses on an experience from Kipnis’s childhood years as a cantorial chorister but ends in the present tense. In the final paragraphs he relates a recent experience of trying to get into a crowded shul late, bringing to light a snapshot of Jewish Warsaw in the interwar period. As related in this anecdote, cantorial performance was a popular audience draw, with a major theater filled to overflow on a Shabbos morning. Indicative of the multicultural space of the urban metropolis, the Polish police officer on duty regulating the crowds was familiar enough with the Hebrew liturgy to know when the service was almost over.

I offer great thanks to David Rheinhold, the cantorial collector par excellence, for alerting me to the existence of this wonderful gem of cantorial cultural history.

*****

Menachem Kipnis, “A shos fun zayn lieben nomen…,” Haynt (March 4, 1938), 8.

A blast from the name of God (lit., a shot from his beloved name)

How Sirota sang for the first time into a gramophone…

A cantorial musical feuilleton.

I saw Sirota for the first time 39 years ago in Vilna.

At the time I was a meshoyrer with the famous Berdichev cantor Zeydel Rovner, with whom I toured the great cities of the former Russia; we also came to Vilna to lead a Sabbath service and give concerts.

We davened in Opatov’s shul. Zeydel Rovner was successful among Vilna’s Jews, who were moved by the Litvish style of khazones, but also loved Zeydel Rovner’s compositions and his style of davening in the Volhynia-Berdichev manner.

The synagogue was full with hundreds of worshippers of householders from Vilna, with dignified broad beards, Litvish Jews.

Among us meshoyrerim on the bime gathered around the cantor there was great interest concerning one person who came to hear us. This was Gershon Sirota, the young cantor of the Shtot shul, the Vilner Shtot Khazn [emphasis in the original].

Forty years ago, to be the Vilna city cantor was a level that very few singers could attain to…the cantorial world was on fire over this Odessan Gershon Sirota, that Vilna had captured. He possessed a one in the world voice. A second Yakov Bachman—people described the wonder—and even greater…

“Sirota is here!” one meshoyrer told the other in the middle of singing—Sirota.

“Where?”

“He’s sitting over there!” There, by the east wall in a corner. After every prayer we sang, the group of meshoyrerim looked over to that corner to see what impression our singing had made on him…and most importantly, to just see him. Such a nature was rare to see among Jews, that of a famous singer, especially among us Berdichever meshoyrerim who were wild fans…

I remember, I was standing on the bimah in an uncomfortable spot where it was harder to see Sirota. After the davening, after all of the householders had left, he came up to us and wished us a bright Good Shabbos, and a fine congratulations. Him—the young hero, the Cantor Gershon Sirota, with his “Good Shabbos,” and “Congratulations”! And then we could see him and consider him up close from all sides…the beautiful legend Gershon Sirota, about whom the people Vilna exaggerated and said when he hit a note in the Great Shul it could actually be heard on Navalne [?].

He was an upstanding young man in his early twenties, neither fat nor thin, but a handsome brunette with a small round beard, that I thought no scissors had ever touched, or if they had it was not apparent…

He made the impression of a young Italian…he wore a fur coat and a top hat. He said his “Good Shabbos” to the cantor alone, to us, the meshoyrerim, he smilingly nodded his head as a kindness.

I remember, I ate him up with my eyes: this is Sirota. The cantor with the living voice. He is the fortunate cantor of Vilna, Jerusalem of Lithuania! All of the weddings, all of the brises, all simchas belong to him…

For a Berdichever meshoyerer this was the greatest fantasy, that he would dream of day and night…

***

I met Sirota two years later.

By that time, I was a meshoyrer in Warsaw in the at that time new shul, Adas Yeshurun. I already had a “petshat.” I had a tenor voice and started to make a little money. The Berdichever Tenor!—people would point at me and say.

One fine day for Warsaw cantors, the musical world was shaken.

Sirota, the Vilna Shtot Khazn, was coming to Warsaw to record into a gramophone. [arayntsuzingn in gramofon.]

Hi famous choir director Leo Leow was coming with him, so that Sirota could be accompanied by a choir on the prayers he would record.

Leo Leow, as a brilliant musician and great expert, was seeking to put together a choir of the best singers in Warsaw. I, the Berdichever, had a place in the choir assembled for the gramophone recording.

I wasn’t as interested in the little bit of money I was earning, as in the opportunity to be heard by Sirota for the first time.

The foreign Gramophone company had taken two room in the Hotel Bristol. In one smaller room was set up the machine that recorded the singing [oyfgekhapt dos gezang] with a long tin tube that stuck out through the door into a second, larger room, where Sirota and Leow with the choir were standing. (This was how the primitive style of recording into a gramophone was carried out. Today it is done very differently…)

By the machine stood the Berlin engineer, a German. He set up the machine and positioned the cantor and choir so that all of their voices would be captured by the tin tube. It took a long time, and I was impatient to hear Sirota.

Apparently in the two years since I saw him in Vilna, Sirota had grown drier, more in the Litvish cantorial style, he was heavier as befit the cantor of the Vilna City Synagogue, he even had a paunch that announced how well Vilner khazones had served him…

He was wearing a long coat of the old Vilna cut. Between his vest and pants stuck out a handsbreadth or two of his talis katan; after all he was the city cantor, and this was about thirty years ago.

Sirota stood around nervously, as though he were carrying stolen goods from a display window. He kept touching his nose, putting a finger on his forehead, making buzzing noises, he trembled—it’s no small thing to record into a gramophone! And as impatient as Sirota was, I was even more impatient—to hear his tone, his singing.

And it came to pass, and it happened, Sirota was placed in front of the tin tube and issues forth a tone. It was a real blast, from the name of God.

I was knocked dead on my feet from the extraordinary craftsmanship that hit my ears. The German engineer ran from the machine to the second room in agitation.

“Stop! You have broken the membrane; the needle was knocked off by your voice!”

The German looked at Sirota in terror, not believing his own ears…

With great courtesy, he positioned Sirota a little further from the tube and asked him to begin again.

Sirota gave a quick tap on the tip of his nose and gave it another shot.

“Stop!” The German ran over again in terror. “You broke the second membrane.”

The German moved Sirota two entire meters away from the tube and asked him to start again.

Sirota opened his mouth and let out a third shot that made windows tremble.

“Stop!” the German ran over again. “You have broken the needle with the wax, that moved from the song…too strong…”

He moved Sirota another three meters away from the tube, to try and reduce the strength of his voice…

And once again, it broke…

Ten membranes broke before Sirota was positioned in a way that wouldn’t damage the membrane with his flaming hot voice.

Then Sirota sang ten or twelve numbers into the gramophone, solos and with the choir. These were the first Gramophone records that made Sirota’s name famous around the world.

——

On Shabbos last week, Sirota davened in the Cinema “Faba.” [newsprint illegible]

I was running late; instead of coming for the rosh khodesh bentshn [the blessing of the new moon], I arrived at the end of musaf [the final section of the Shabbos morning service] and the policeman stationed at the door wouldn’t let me in.

“Już koniec,” [Polish, it’s over] said the policeman and directed me away.

“Is Retse over?” I asked a Jew who emerged all sweaty.

“Już!” said the policeman and drove me away “Wszystko już śpiewał.” [Polish, he already sang everything.]

As the doors of the movie theater opened a powerful tone emanated outside.

“B’shalom!!!” Sirota ended the davening on an exceptionally long high C. “Hamevorakh es amo yisroel b’shalom!” [Hebrew, who blesses His people Israel with peace; the final words of the cantor’s repetition of the amidah prayers that end the musaf service].

It’s been more than thirty years since I first heard that phenomenal tone for the first time in the Hotel Bristol.

Jews, this voice is still a blast, from the name of God.