Pesach in Brooklyn: Hefker and Khazones in the Barroom

This past week, on Tuesday April 15, a special gathering took place in the back room of Barbes, a small bar and music venue in Brooklyn. The gathering was an invitation-only circle of singers who are involved with khazones (the Yiddish term for cantorial art music) either as synagogue practitioners or as performers of historically informed Yiddish vocal music. The group was convened as part of a new organization called Khazones Underground, founded by me and Judith Berkson, a cantor and noted composer of contemporary art music. Khazones Underground is an arts activism organization focused on promoting cantorial revival through releasing new albums of khazones and by producing concerts and educational events. The organization is something Judith and I have been discussing for years and that we have taken steps to formally launch, beginning with a tour of the Bay Area this past February.

We described the gathering at Barbes as a cantorial kumsitz, a term for a music making party, something that occurs with some regularity in the Hasidic community. The cantorial kumsitz party is characterized by individuals taking turns singing solo material, typically based on canonical phonograph recordings of cantors from the early 20th century. As I discuss in my recent book Golden Ages, because khazones is rarely performed in contemporary synagogues, cantorial kumsitz parties are particularly important as a music making opportunity for Hasidic singers in this underground musical revival movement.

Unlike Hasidic cantorial kumsitz parties, which take place in an all-male social environment, the Khazones Underground gathering was open to people from a variety of identities and backgrounds. The group included singers who grew up in the Hasidic community, Rikki Rose and Yoel Kohn, both of whom are brilliant performers of khazones, as well as clergy from the liberal movements, Yiddishists, and others. The gathering was a kind of test of concept of the Khazones Underground mission, which is to gather and promote voices of cantorial revival from a variety of corners of the Jewish world, and to connect singers with overlapping musical visions to each other.

The gathering started with Judith Berkson leading vocal exercises in which participants acted as a choir singing drones and individuals were invited to improvise over conducted chord changes. Then we heard individual performances of cantorial repertoire, including a stellar rendition of Yossele Rosenblatt’s Vehu Rachum (originally recorded in 1928) sung by Riki Rose, Alter Karniol’s Tal (1914) by Yoel Kohn, Yehoshua Meisel’s Birkas Kohanim (1907) sung by vocalist and composer Eli Berman, and Cantor Zachary Konigsberg singing a rendition of L’dor V’dor he learned from his grandfather Cantor Jacob Konigsberg (Zachary and I are cousins, and both studied with our grandfather). The group of singers was rounded out by Hadar Ahuvia, an accomplished dancer and rabbinic intern at a Brooklyn synagogue, Cantor Sarah Myerson, and Sarah Larsson, a singer and folklorist.

Performing khazones, for singers at the Khazones Underground gathering and in the Hasidic cantorial revivalist scene, is a musical counterculture. Today, Jewish liturgical music is in a period of great productivity and renewal. However, the mainstream of Jewish American music, both in Hasidic and liberal communities, gravitates towards styles that are, broadly speaking, appropriative of sounds derived from contemporary pop music and Protestant hymn styles of unison metered melodies. In contrast, the sounds of cantorial revival are rooted in historically informed soloist vocal performance, heavily dependent on intermundane collaboration with the recorded voices of dead cantors and other Jewish voices from the early 20th century, entwined with the social history of Yiddish culture and the transnational diaspora of Ashkenazi Jews, and stubbornly at odds with the norms of contemporary Jewish life. In the contemporary Jewish American moment, creating sounds of khazones bears a stamp as an act of aesthetic and social rebellion. For each of the artists I have met and worked with who are involved in cantorial revival, khazones holds a different shade of meaning. The goals of cantorial revival, as represented by the individuals who came to the gathering at Barbes, range from projects of constructing Jewish identity drawing on a conception of historical diaspora experience, to aesthetic goals of establishing artistic voices and careers through the study of the cantorial canon, to gender liberation activism relating to the limitations placed on women’s voices singing sacred music in traditionalist Jewish communities. For all of the singers, khazones is a shared object of desire, presenting a mystically charged musical vision of a sacred but starkly visceral and embodied approach to the act of representing Jewish collectivity in conversation with the Divine.

Upholding and honoring the voices and aspirations of cantorial revivalists is at the core of the mission of Khazones Underground. The gathering at Barbes could be the subject of its own ethnography; however I will defer that lengthier project until a future date. In the space of this brief blog post I will instead try to recall the words of introduction that I gave by way of explanation and intention setting for the gathering.

My speech took as its theme hefker, a Talmudic term for abandoned property which came to be used in an anti-commercialism and anti-vulgarization discourse aimed at the phonograph era cantorial stars. As I have written about elsewhere, cantors are vulnerable to accusations of corrupting tradition. This is in part because cantors are actively involved in a constant process of transformation of the musical landscape of ritual, responding to shifting structures of feeling in the world of art and society. Cantors are musical representatives of the community who are involved in projects of heritage preservation, and of experimentation and adoption of musical sounds from the majority non-Jewish population into the culturally intimate space of the Jewish synagogue. The tension between these two aesthetic imperatives in the work of cantors make them vulnerable to criticism on a variety of levels ranging from ritual impurity to inadequate receptivity to changing tastes in contemporary music.

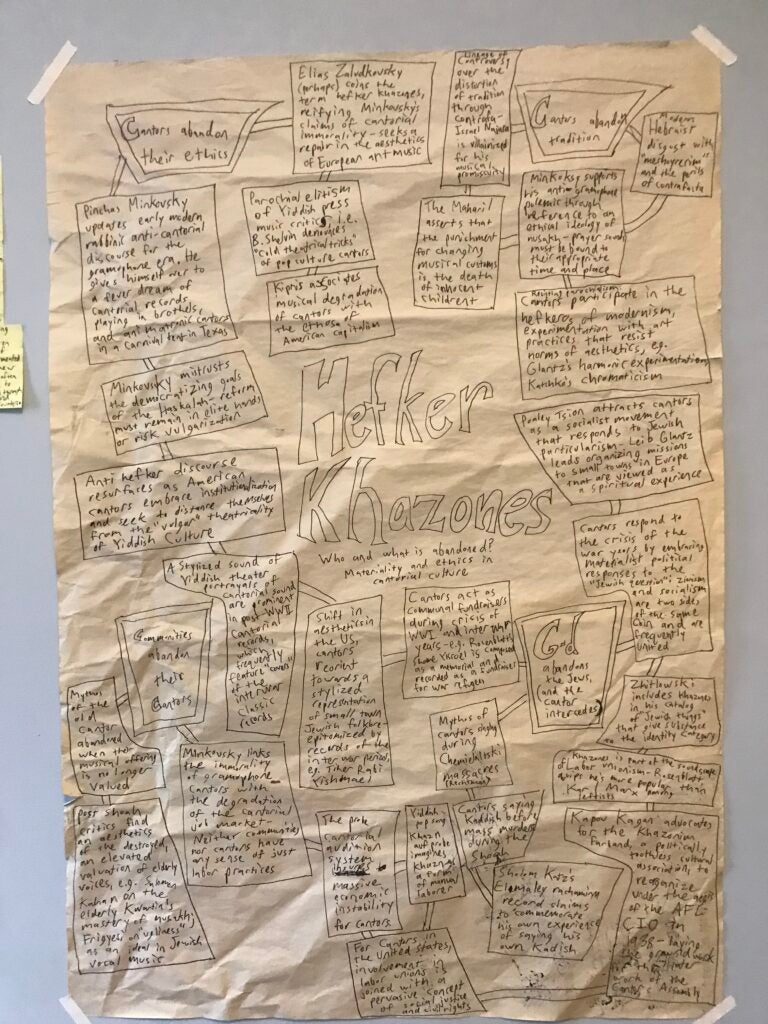

I take seriously the category of hefker khazones, that appears in the writings of Cantor Elias Zaludkovsky (1888-1943), Cantor Pinchas Minkovsky (1859-1924) and other Yiddish critics of the early 20th century cantorial pop culture period. Zaludkovsky, who seems to have coined the term, used the accusation of hefker to distinguish himself from his peers who he disparaged as vulgarizing and demeaning the tradition by trafficking in populism, cheap theatrical tricks, and by bringing sacred sound into inappropriate contexts. In my current research, hefker is a central analytical tool that I use to explore the meaning of changes in cantorial culture. What I seek to understand about hefker khazones is who and what is being abandoned. In a visual concept map that I currently have hanging up in my room, I explore the topic of hefker through three categories of cantorial abandonment: cantors abandoning tradition, Jews abandoning their cantors, and God abandoning the Jews with cantors playing a heightened role as intermediaries seeking repair of the ruptured relationship through musical and political interventions.

My short talk at the cantorial kumsitz was topical: hefker is a relevant term for the Passover holiday that we are now just ending. After one cleans one’s home before Pesach to make sure there is no bread or other leavened food items that are prohibited on the holiday, a special prayer is said that declares any chomets (leavened food) still in your home to be hefker, that is to say it is no longer the possession of oneself or anyone else. This state of declared, formalized abandonment is a key to understanding the concept of hefker and of the particular emotional economy of cantorial performance.

In halachic (Jewish legal) discourse in the Talmud, there are a series of four legal maneuvers by which something can become hefker: by someone renouncing their ownership, by someone losing something, by something being taken away by a rabbinic court as a punishment, or through an act of God’s creation, for example, the naturally occurring phenomena of the mountains or the desert, which cannot be created by man and therefore cannot be owned.

Beyond these categories, the term hefker carries certain moods that inflect its legal status and that later came to influence the use of the term in the Yiddish language. On the one hand, hefker is commonly understood to refer to sexual abandonment. Specifically, in Talmudic discourse hefker refers to the sexuality of a woman who is not contained by being the “possession” of a man in marriage. In Yiddish, the word hefker is sometimes used in this sense, to convey the idea of sexual licentiousness.

On the other hand, hefker carries an association with divine revelation. In the Midrash to the Book of Numbers, it is explained that revelation only occurs in places that are hefker, the classic example being the giving of the Torah on Mt. Sinai. The Midrash extends this idea, stating that in order to receive revelation, an individual too must become hefker, here signifying a state of being ownerless or of spiritual freedom.

I concluded my talk by suggesting that the problems and the great possibilities of khazones as an expressive art form lie in its relationship to these two moods of hefker. Khazones, particularly in its aestheticized form as a popular performance genre, is characterized by sensual excess and extremes, producing an eroticized mode of performance that pushes at norms of public comportment to achieve extremes of expressive power. The cantorial voice defies norms of gender, performing a stylized sound of hyper-emotional Jewish vocal expression that is piquantly at odds with modern European norms of masculine restraint.

This unrestrained quality of the cantor’s voice makes it akin to those places of wildness that are the appropriate place of revelation. This quality of being akin to nature is especially relevant in the cantor’s quality of memorialization. When the world is overrun by violence and humanity itself is rendered hefker and abandoned by Divine laws of justice, cantors intercede as a voice of memory that focuses the experience of pain into a productive experience of catharsis and social organization in the form of a sacred community.

These were the intentions that I brought to the community of singers as we began the music making party, seeking to connect my research and interpretations of the cantorial golden age into conversation with the artists who are making this musical legacy live. As we proceeded into the singing, it became clear that a breadth of powerful musical visions were present in the room. This gathering, intended to be the first of many events that will draw together cantorial revivalist voices, was intentionally partial and provisional. The work of cantorial revival is unfolding; I am very excited to be witnessing this scene of artists as they proceed to create new musical and ritual communities and expressions.